About

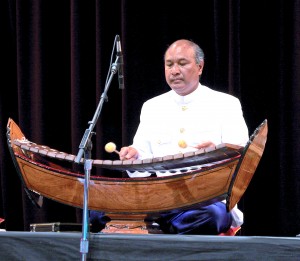

Chum Ngek is Cambodian music master with a vast repertoire from the major Cambodian music genres: pin peat, mohori, and phleng kar. He plays and teaches multiple instruments and is interested in passing on traditions while engaging in new creative work.

Chum Ngek is one of the few living Khmer music masters worldwide who possesses a vast repertoire and command of multiple instruments across various genres. He is the 2004 recipient of the Bess Lomax Hawes Award, the NEA National Heritage Fellowship conferred upon one artist who has significantly benefited his or her tradition through teaching and preserving important repertoires. Chum has also received honors from The Maryland State Arts Council and the Arts and Humanities Council of Montgomery County.

Born in Battambang Province, Cambodia, Chum first formally studied the repertoire and instruments of the major Khmer musical genres—pin peat, mohori, and phleng kar—at the age of ten under his grandfather, Um Hieng. Under his grandfather’s guidance, Chum learned to perform pin peat repertoire on the sralai, kong thom, and sampho. He also studied kong thom, sampho, and skor thom under Master Oeur, who was a cousin of Chum’s grandfather. Although Chum’s grandfather did not want him to become a professional musician, his talent and love for music could not be denied. Consequently, Chum’s grandfather set up private apprenticeships for him with the province’s best musicians. At the age of twelve, Chum so impressed his teacher, Master Chou Nit (a roneat aik master) that he learned Homrong (a series of sacred songs that are pivotal to the Khmer classical music tradition known as pin peat) in the same year.

Although Chum considered Master Nit to be his primary teacher, he continued to broaden his knowledge of kong thom with Master Ton and his skills on the roneat aik under Master Chhuorm and Master Van. By the time he was eighteen, Chum began to perform professionally and lead ensembles. There was no longer any reason for his grandfather to worry about whether or not he would succeed as a musician. Instead, Chum was earning a handsome living even before he finished high school. As an employee of his province, Chum provided music for official ceremonies and social functions. He also performed in other provinces, spending weeks at a time “on the road.” In 1974, Chum was selected as his region’s representative for a national music contest and artist residency held at the Royal University of Fine Arts in Phnom Penh.

In 1975, the Khmer Rouge cut short Chum’s promising career. Pol Pot and his army deluded Battambang’s citizens into abandoning their urban homes and moving to the villages to embark upon a collectivized socioeconomic experiment. Under this new system, the family unit was dissolved and religion was banned. Further, city-‐dwellers, intellectuals, capitalists, and former government officials were executed, because they were considered to be potential enemies of the revolution. Incredibly, Chum Ngek survived for four years under such conditions, in part, because of his musical abilities. To this day, he vividly recalls at least two occasions on which his good relations with a Khmer Rouge leader, who was also a musician, had saved his life.

When the Khmer Rouge lost power in 1979, returning to life as it was prior to 1974 was not an option. Chum initially tried to reclaim his career as a musician, but eventually he turned to relocating with his family to Thai refugee camps. In Khao I Dang camp, he contributed his musical talents to teaching and performing activities. He even taught and performed in Galang, a refugee camp in Indonesia, which was Chum’s final stop before immigrating to the United States.

Chum’s move to the United States was facilitated by a request for his services by the Khmer Classical Dance Troupe, with which he worked during his stay in Khao I Dang camp. The company, which resettled together in the United States, was committed to touring the country, yet it could not do so without a skilled music director. In response to this dilemma, the troupe’s sponsoring organizations expedited Chum’s journey from Indonesia.

Since arriving in the United States in June 1982, Chum has been active advising, teaching, and performing across the country. He has been a key informant for research and educational materials that document Khmer music, including projects that have helped to revive traditional music in Cambodia. He performs regularly in venues such as the Kennedy Center, Smithsonian Institution, and National Folk Festival; provides music for Khmer traditional weddings and religious ceremonies; and performs for and teaches weekly at the Cambodian American Heritage Inc. in Virginia and Cambodian Buddhist Society, Inc. in Maryland. Chum’s role in these organizations and others across the country extends far beyond mere performance: As the bearer of an endangered tradition, he is the consultant for them, providing guidance about appropriate repertoire and style for each event. Moreover, even when he cannot physically be in more than one place at a time, Chum actually manages to make himself present in various locations by providing students and dance instructors with recordings of his music.